A Black Women's History of the United States (OBOC 2021-2022)

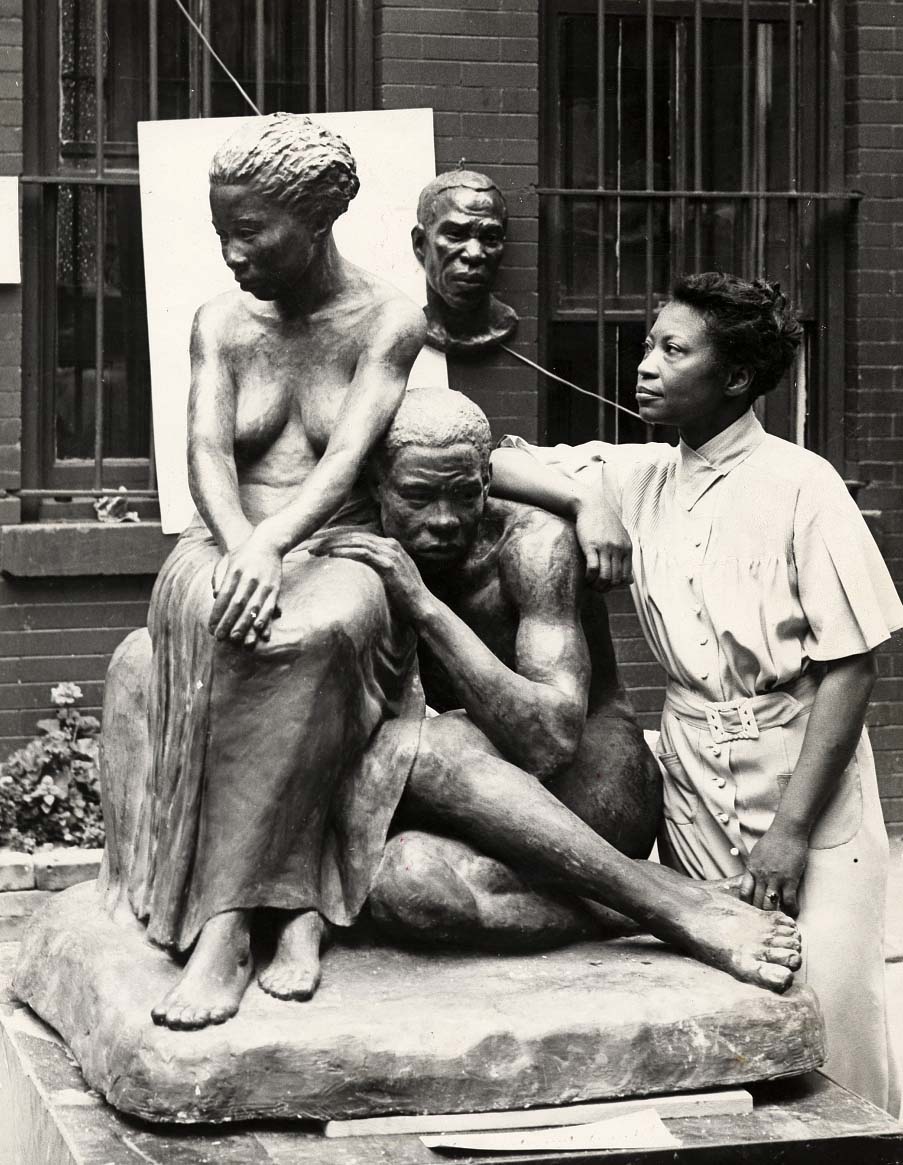

Chapter Seven: Augusta’s Clay, Migration, and the Depression, 1915-1940

Black Queer women in the migration

Ma Rainey

Nannie Helen Burroughs/National League of Republican Colored Women

Amy Ashwood Garvey: (wife #1 Marcus Garvey)

Amy Jacques Garvey: (wife #2 Marcus Garvey)

Black women domestic workers 1930s

Pecan Factory Fight

Documents:

There are other documents found in the links associated with individual names as well.

“All the Colored Women Like This Work”: Black Workers During World War I

Wartime production demanded the mobilization of thousands of workers to make steel and rubber, to work in petrochemical industries, and to build ships. As a result, African Americans made striking gains in employment even while also facing continuing discrimination. Black women, for example, got jobs working on the railroads for the first time during the world war. Black women found jobs as laborers, cleaning cars, wiping engines, tending railroad beds. Helen Ross was one of them, working for the Santa Fe Railroad. In an interview with the Women’s Service Section of U.S. Railroad Administration, Ross described the advantages of her railroad job. Nevertheless, the same agency later declared such work too heavy for women.

"All the colored women like this work and want to keep it. We are making more money at this than any work we can get, and we do not have to work as hard as at housework which requries us to be on duty from six o’clock in the morning until nine or ten at night, with might little time off and at very poor wages....What the colored women need is an opportunity to make money. As it is, they have to take what employment they can get, live in old tumbled down houses or resort to street walking, and I think a woman ought to think more of her blood than to do that. What occupation is open to us where we can make really good wages? We are not employed as clerks, we cannot all be school teachers, and so we cannot see any use in working our parents to death to get educated. Of course we should like easier work than this if it were opened to us, but this pays well and is no harder than other work open to us. With three dollars a day, we can buy bonds..., we can dress decently, and not be tempted to find our living on the streets..."

Source: quoted in Maurine Weiner Greenwald,Women, War, and Work: The Impact of WW I on Women Workers in the United States(Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980).from interview by Helen Ross, Freight House, Santa Fe RR, Topeka, KS, 28 October 1918: 27 File 55, Women’s Service Section, RG 14, National Archives, Washington, DC.

One Book One College Discussion/Essay/Reflection Prompts:

1. Chapter Seven discusses the accomplishments and contributions of numerous Black women to the arts. Select one of these women and read more about her. Investigate the corresponding links in the library guide to assist your research. In what ways does the artist’s work represent her experience? Depending upon the artist’s medium, take some time to view, read, or listen to her craft. Do you see struggle, resilience, celebration and/or affirmation in her work?

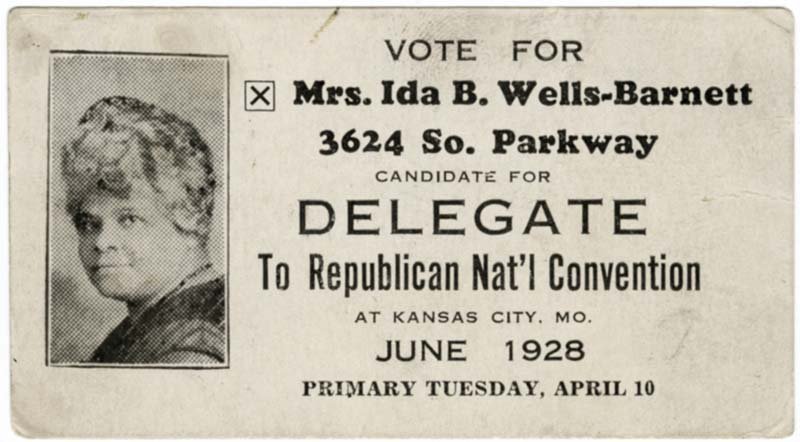

2. Facets of political activism, including those connected to federal programs and suffrage movements, are discussed in Chapter Seven. How did these programs advance or derail the progress of Black women? Who led? Who impeded? Who worked as allies?

3. Berry and Gross write, “Throughout the early twentieth century, African American women remained overrepresented in the justice system. And though the 1920s witnessed a pronounced move toward reformatories for women convicted of crimes, Black women and Black girls often went to custodial institutions, as administrators believed them to be biologically unredeemable” (132). How and when was this injustice corrected? Investigate present-day incarceration and parole statistics and determine if real change has occurred.

4. This chapter addresses the migration of Black women. Identify some of the areas from which and to which Black women moved. What were the catalysts of these moves? How did urban life differ from or compare to rural life? What dynamics were at play in these areas? Were those who moved welcomed to their new communities?

5. How does Augusta (Fells) Savage’s experience symbolize the path of Black women who had to flee their homes and mask their authentic selves in order to survive?

6. Discuss the appeal of different political parties and of different political leaders to Black women. How did Black women feel supported or maligned by these different groups and leaders?

7. Throughout our reading of A Black Women’s History of the United States, we have seen the important role of oral and written history formed in interviews, court documents, transcripts, songs, etc., to document the lives of many of these women. How does your family share its history? How is your family’s history preserved for the edification of future generations? Is there a living family member you’d like to interview to learn more about the person? What insight does this individual hold?

Gladys Bentley

-

Gladys Bentley: Gender-Bending Performer and Musician(this includes a short video clip of her tv appearance on Groucho Marx show)

Ida B. Wells and women's suffrage movement

Black women in the suffrage movement

Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke

-

The CRISIS- this is the issue of the Crisis that includes their essay on the Bronx Slave Market

Marvel Cooke:

Series of articles from 1950

Ella Baker

Later work with SNCC

Marvel Cooke

-

Marvel Cooke oral history interview(this contains the pdf for her oral history)

Black women and the Communist Party

Fannie Peck/Detroit Housewives League

Claudia Jones

Jim Crow in Uniform pamphlet by Claudia Jones:

-

Jim Crow in UniformWRITTEN BY

Jones, Claudia, American, 1915 - 1964

Additional Reading:

Deirdre Bloome, James Feigenbaum and Christopher Muller, “Tenancy, Marriage, and the Boll Weevil Infestation, 1892–1930” Demography, Vol. 54, No. 3 (June 2017), pp. 1029-1049 (21 pages)

Katherine J. Curtis, “Women in the Great Migration: Economic Activity of Black and White Southern-Born Female Migrants,” Social Science History, vol. 29, no. 3 (Oct. 2005): 413-455.

Nina Banks, “Uplifting the race through domesticity: Capitalism, African-American migration, and the household economy in the Great Migration era of 1916–1930.” Feminist Economics, [s. l.], v. 12, n. 4, p. 599–624, 2006.

Elizabeth Clark-Lewis, Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration, (NY: Kodansha International, 1996) UNLV has a copy

Nikki L. M. Brown, Private Politics and Public Voices: Black Women’s Activism from World War I to the New Deal (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2006). UNLV has a copy

Hazel V. Carby, “Policing the Black Woman’s Body in an Urban Context,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 18, no. 4 (July 1992): 738-755.

Cookie Woolner, “’Woman Slain in Queer Love Brawl:’ African American Women, Same-Sex Desire, and Violence in the Urban North,” The Journal of African American History, vol. 100, no. 3 (June 2015): 406-427.

LaShawn Harris, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Number Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016) CSN online access

Treva Lindsey, Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, DC (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017) CSN online access

Ula Y. Taylor, The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002) UNLV

Keisha N. Blain. “’We Want to Set the World on Fire:’ Black Nationalist Women and Diasporic Politics in the “New Negro World,” 1940-1944” Journal of Social History, vol. 49, no. 1 (Oct. 2015): 194-212.