A Black Women's History of the United States (OBOC 2021-2022)

Chapter Five: Mary’s Apron and the Demise of Slavery, 1860–1876

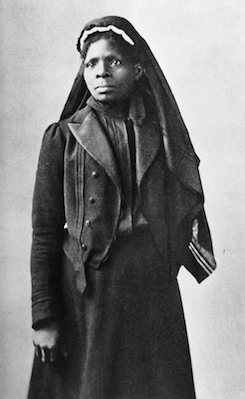

Mary Colbert

Sarah Jane Woodson Early

Sojourner Truth’s Famous Speech: Ar’n’t I A Woman? – Ain’t I a Woman?

Sojourner Truth gave what is now known as her most famous speech at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, but it is questionable that she said the words, “Ain’t I a Woman?” or even “Ar’n’t I A Woman?” No actual record of the speech exists, but Frances Gage, an abolitionist and president of the Convention (and also a poet), recounted Truth’s words in the National Anti-Slavery Standard, May 2, 1863. The accuracy of this account has been challenged for several reasons: the delayed time–twelve years after the event took place, Gage’s use of a southern dialect, choice of language, and some clear errors about Sojourner’s life. Gage reports Sojourner saying she had “borne 13 children and seen ‘em mos’ all sold off to slavery,” but she had five children; one was sold and then his mother went to court and got him back.

Several newspaper reports about Sojourner’s speech have been found that were written shortly after the event. The most detailed one below, from the Salem, Ohio, Anti-Slavery Bugle, was written by Marcus Robinson, a friend of Sojourner’s who heard the speech. Though there are clear differences in the two accounts, most of the important themes are the same. An account of Gage’s version appears in the 1875 reprinting of Truth’s Narrative and Book of Life. Later “Reminisces by Frances D. Gage” was published in the History of Women’s Suffrage, (1881) Vol. 1, 115-117, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda J. Gage.

Additional Reading

Heather Andrea Williams, "'Clothing Themselves in Intelligence;': The Freedpeople, Schooling and Northern Teachers, 1861-1871," vol. 87 Journal of African American History (Autumn 2002): 372-389.

Anna Marie Brosnan, “’To Educate Themselves:’ Southern Black Teachers in North Carolina’s Schools for the Freedpeople During the Civil War and Reconstruction Period, 1862-1875,” American Nineteenth Century History, vol. 20 no. 3 (Sept. 2019): 231-248.

Mary Farmer-Kaiser, “’With a Weight of Circumstances like Millstones about Their Necks’: Freedom, Federal Relief, and the Benevolent Guardianship of the Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 115, no. 3 (Jan. 2007): 412-442.

Thaviola Glymph, “’I’m a Radical Black Girl’: Black Women Unionists and the Politics of Civil War History,” Journal of the Civil War Era, vol. 8, no. 3 (Sept. 2008): 359-387.

Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom (NY: Back Bay Books/Little Brown, 2005). NLV campus has a copy of this book.

UNLV has the books by

Rosalind Terborg-Penn and Nell Irvin Painter, mentioned in the endnotes to Chapter 5.

“The Evil Shadow of Slavery No Longer Hangs Over Them”: Charlotte Forten Describes Her Experiences Teaching on the South Carolina Sea Islands, 1862

During the Civil War, when Union forces occupied the South Carolina sea islands of St. Helena and Port Royal, white slaveowners fled but their slaves remained. It was here, in October 1862, that Charlotte Forten arrived under the auspices of the Philadelphia Port Royal Relief Association to teach the newly liberated slaves. Forten (later Charlotte Forten Grimke) was born in Philadelphia in 1837 into a family of well-to-do, free blacks who were active in the abolitionist movement. Forten was a teacher and a writer, known today for her extensive diaries and her articles. An educated woman and a product of free black society, Forten hovered uneasily between the worlds of blacks and whites. In this article for a white audience she expressed her jubilation about the freedom her students were newly experiencing. She also revealed her ambivalence about these people who were similar to herself, yet at the same time so different.

The first day at school was rather trying. Most of my children were very small, and consequently restless. Some were too young to learn the alphabet. These little ones were brought to school because the older children — in whose care their parents leave them while at work — could not come without them. We were therefore willing to have them come, although they seemed to have discovered the secret of perpetual motion, and tried one’s patience sadly. But after some days of positive, though not severe treatment, order was brought out of chaos, and I found but little

difficulty in managing and quieting the tiniest and most restless spirits. I never before saw children so eager to learn, although I had had several years' experience in New England schools. Coming to school is a constant delight and recreation to them. They come here as other children go to play. The older ones, during the summer, work in the fields from early morning until eleven or twelve o’clock, and then come into school, after their hard toil in the hot sun, as bright and as anxious to learn as ever.

Of course there are some stupid ones, but these are the minority. The majority learn with wonderful rapidity. Many of the grown people are desirous of learning to read. It is wonderful how a people who have been so long crushed to the earth, so imbruted as these have been, — and they are said to be among the most degraded negroes of the South, — can have so great a desire for knowledge, and such a capability for attaining it. One cannot believe that the haughty Anglo Saxon race, after centuries of such an experience as these people have had, would be very much superior to them. And one’s indignation increases against those who, North as well as South, taunt the colored race with inferiority while they themselves use every means in their power to crush and degrade them, denying them every right and privilege, closing against them every avenue of elevation and improvement. Were they, under such circumstances, intellectual and refined, they would certainly be vastly superior to any other race that ever existed.

After the lessons, we used to talk freely to the children, often giving them slight sketches of some of the great and good men. Before teaching them the “John Brown” song, which they learned to sing with great spirit. Miss T. told them the story of the brave old man who had died for them. I told them about Toussaint, thinking it well they should know what one of their own color had done for his race. They listened attentively, and seemed to understand. We found it rather hard to keep their attention in school. It is not strange, as they have been so entirely unused to intellectual concentration. It is necessary to interest them every moment, in order to keep their thoughts from wandering. Teaching here is consequently far more fatiguing than at the North. In the church, we had of course but one room in which to hear all the children; and to make one’s self heard, when there were often as many as a hundred and forty reciting at once, it was necessary to tax the lungs very severely.

My walk to school, of about a mile, was part of the way through a road lined with trees, — on one side stately pines, on the other noble live-oaks, hung with moss and canopied with vines. The ground was carpeted with brown, fragrant pine-leaves; and as I passed through in the morning, the woods were enlivened by the delicious songs of mocking-birds, which abound here, making one realize the truthful felicity of the description in “Evangeline,” —

"The mocking-bird, wildest of singers, Shook from his little throat such floods of delirious music That the whole air and the woods and the waves seemed silent to listen."

The hedges were all aglow with the brilliant scarlet berries of the cassena, and on some of the oaks we observed the mistletoe, laden with its pure white, pearl-like berries. Out of the woods the roads are generally bad, and we found it hard work plodding through the deep sand.

Source: Charlotte Forten, “Life on the Sea Islands,” Atlantic Monthly 13 (May 1864): 587–596.

WPA slave Narrative

-

Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938Robust site with a number of narratives gathered in the 1930s, this also includes information on post-slavery and useful for chapter 6 as well.

Edmonia Lewis

“Women Rights Convention. Sojourner Truth.” Anti-Slavery Bugle, Salem, Ohio, June 21, 1851 – Marcus Robinson

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: “May I say a few words?” Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded:

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes

being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart — why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, — for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

Chapter 5: Discussion/Essay/Reflection Prompts

1. The freedom granted the enslaved in April 1865 was met with considerable pushback by planters in need of forced laborers and by terrorist groups unwilling to surrender their hate. Explore the efforts made by the then newly formed Ku Klux Klan and other opponents to the Radical Reconstruction (“Ku Klux Klan Violence in Georgia, 1871”) to instill fear and circumvent the law. Read the transcript in the Library Guide of Maria Carter’s testimony and identify at least two of Carter’s answers that shed insight into the fear that persisted among the freed slaves. Then discuss why the Klan still persists in 2021. In what ways does their behavior persist in harming society?

2. What is the significance of June 19, 1865? What is the significance of June 19, 2021? What does this span of time between the dates tell us about the path to freedom?

3. Name a few of Edmonia Lewis’s contributions to social justice and art. Refer to the discussion on pages 97-98 of the Berry and Gross work and the content of the following links: Edmonia Lewis’s contributions to social justice and art and Wildfire Mary Edmonia Lewis

4. Compare and contrast the abolitionist efforts of Harriet Tubman (born enslaved) and Charlotte Forten Grimké (born free). Be sure to investigate the Grimké links within the guide.

5. Keeping in mind the accounts of Mary Colbert’s life provided at the beginning and end of Chapter Five, consider young and adult Mary’s capacity for reflection. Discuss her ability to endure and accept her circumstances by writing a brief paragraph or a poem.

Charlotte Forten Grimke

-

Journal of Charlotte Forten, Free Woman of ColorThis includes a selection from her journal.

Juneteenth

-

Juneteenth - A celebration of resilienceThis includes some video clips and other resources about Juneteenth

Ku Klux Klan Violence in Georgia, 1871

Following the Civil War, the federal government brought newly freed people into the political and economic sphere through a variety of efforts known as Radical Reconstruction. But planters, unwilling to lose control over African-American laborers, attempted to rule the South through violence and legal and economic intimidation. The secret terrorist organization the Ku Klux Klan was part of the violent white reaction to Reconstruction. Founded by Confederate veterans in Tennessee in 1866, Klan nightriders targeted black veterans and freedmen who had left their employers and those who had succeeded in breaking out of the plantation system. African Americans who transgressed local norms of white supremacy were in particular danger as the testimony from Maria Carter and others at these 1871 Congressional hearings about the Klan made clear. Klan leaders often were prominent planters and their family members while poorer men made up the rank and file.

Atlanta, Georgia, October 21, 1871

MARIA CARTER (colored) sworn and examined.

By the Chairman:

Question. How old are you, where were you born, and where do you now live?

Answer. I will be twenty-eight years old on the 4th day of next March: I was born in South Carolina; and I live in Haralson County now.

Question. Are you married or single?

Answer. I am married.

Question. What is your husband’s name?

Answer. Jasper Carter.

Question. Where were you on the night that John Walthall was shot?

Answer. In my house, next to his house; not more than one hundred yards from his house.

Question. Did any persons come to your house that night?

Answer. Yes, sir, lots of them; I expect about forty or fifty of them.

Question. What did they do at your house?

Answer. They just came there and called; we did not get up when they first called. We heard them talking as they got over the fence. They came hollering and knocking at the door, and they scared my husband so bad he could not speak when they first came. I answered them. They hollered, “Open the door.”I said, “Yes, sir.” They were at the other door, and they said, “Kindle a light.” My husband went to kindle a light, and they busted both doors open and ran in—two in one door and two in the other. I heard the others coming on behind them, jumping over the fence in the yard. One put his gun down to him and said, “Is this John Walthall?” They had been hunting him a long time. They had gone to my brother-in-law’s hunting him, and had whipped one of my sisters-in-law powerfully and two more men on account of him. They said they were going to kill him when they got hold of him. They asked my husband if he was John Walthall. He was so scared he could not say anything. I said, “No.” I never got up at all. They asked where he was, and we told them he was up to the next house, they jerked my husband up and said that he had to go up there. I heard them up there hollering “Open the door,” and I heard them break the door down. While they were talking about our house, just before they broke open our door, I heard a chair fall over in John Walthall’s house. He raised a plank then and tried to get under the house. A parcel of them ran ahead and broke the door down and jerked his wife out of the bed. I did not see them, for I was afraid to go out of doors. They knocked his wife about powerfully. I heard them cursing her. She commenced hollering, and I heard some of them say, “God damn her, shoot her.” They struck her over the head with a pistol. The house looked next morning as if somebody had been killing hogs there. Some of them said “Fetch a light here, quick;” and some of them said to her, “Hold a light.” They said she held it, and they put their guns down on him and shot him. I heard him holler, and some of them said, “Pull him out, pull him out. ” When they pulled him out the hole was too small, and I heard them jerk a plank part off the house and I heard it fly back. At that time four men came in my house and drew a gun on me; I was sitting in my bed and the baby was yelling. They asked, “Where is John Walthall?” I said, “Them folks have got him.” They said, “What folks?” I said, “Them folks up there.” They came in and out all the time. I heard John holler when they commenced whipping him. They said, “Don’t holler, or we’ll kill you in a minute.” I undertook to try and count, but they scared me so bad that I stopped counting; but I think they hit him about three hundred licks after they shot him. I heard them clear down to our house ask him if he felt like sleeping with some more white women; and they said, “You steal, too, God damn you.” John said, “No, sir,” They said, “Hush your mouth, God damn your eyes, you do steal.”I heard them talking, but that was all I heard plain. They beat him powerfully. She said they made her put her arms around his neck and then they whipped them both together. I saw where they struck her head with a pistol and bumped her head against the house, and the blood is there yet. They asked me where my husband’s gun was; I said he had no gun, and they said I was a damned liar. One of them had a sort of gown on, and he put his gun in my face and I pushed it up. The other said, “Don’t you shoot her. ” He then went and looked in a trunk among the things. I allowed they were hunting for a pistol. My husband had had one, but he sold it. Another said, “Let’s go away from here.” They brought in old Uncle Charlie and sat him down there. They had a light at the time, and I got to see some of them good. I knew two of them, but the others I could not tell. There was a very large light in the house, and they went to the fire and I saw them. They came there at about 12 o’clock and staid there until 1. They went on back to old Uncle Charley’s then, to whip his girls and his wife. They did not whip her any to hurt her at all. They jabbed me on the head with a gun, and I heard the trigger pop. It scared me and I throwed my hand up. He put it back again, and I pushed it away again.

Question. How old was your baby?

Answer. Not quite three weeks old.

Question. You were still in bed?

Answer. Yes, sir; I never got up at all.

Question. Did they interrupt, your husband in any way?

Answer. Yes, sir; they whipped him mightily; I do not know how much. They took him away up the road, over a quarter, I expect. I saw the blood running down when he came back. Old Uncle Charley was in there. They did not carry him back home. They said, “Old man, you don’t steal.” He said, “No.” They sat him down and said to him, “You just stay here.” Just as my husband got back to one door and stepped in, three men came in the other door. They left a man at John’s house white they were ripping around. As they came, back by the house they said, “By God, goodbye, hallelujah!” I was scared nearly to death, and my husband tried to keep it hid from me. I asked him if he had been whipped much. He said, “No.” I saw his clothes were bloody, and the next morning they stuck to him, and his shoulder t almost like jelly.

Question. Did you know this man who drew his gun on you?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Who was he?

Answer. Mr. Much.

Question. Where does he live?

Answer. I reckon about three miles off. I was satisfied I knew him and Mr. Hooker.

Question. Were they considered men of standing and property in that country?

Answer. Yes, sir; Mr. Finch is married into a pretty well-off family. He is a good liver, but he is not well off himself.

Question. How is it with Mr. Booker?

Answer. I do not know so much about him. He is not very well off.

Question. How with the Monroes?

Answer. They are pretty well-off folks, about as well off as there are in Haralson. They have a mill.

By Mr. BAYARD:

Question. You said they had been looking a long time for John Walthall ?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Had they been charging John with sleeping with white women?

Answer. Yes, sir; and the people where he staid had charged him with it. He had been charged with it ever since the second year after I came to Haralson. I have been there four years this coming Christmas.

Question. That was the cause of their going after him and making this disturbance?

Answer. Yes, sir; that was it. We all knew he was warned to leave them long before he was married. His wife did not know anything about it. When he first came there he was staying among some white women down there.

Question. Do you mean living with them and sleeping with them?

Answer. He was staying in the house where they were.

Question. White women?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Were they women of bad character?

Answer. Yes, sir; worst kind.

Question. What were their names?

Answer. They were named Keyes.

Question. How many were there?

Answer. There were four sisters of them, and one of them was old man Martin’s wife.

Question. Were they low white people?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Had John lived with them for a long while?

Answer. Yes, sir. They had threatened him and been there after him. They had got gone there several times to run them off. My house was not very far from them, and I heard them down there throwing rocks.

Question. Was it well known among you that John had been living with these low white women?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Did he keep it up after he was married?

Answer. No, sir; he quit before he was married. I heard that a white woman said be came along there several times last year and said he could not get rid of them to save his life.

Question. Did John go with any other white women?

Answer: No, sir; not that I know of.

Question. Was he accused by the Ku-Klux of going with any of them?

Answer. They did not tell him right down their names. I heard them say, “Do you 'feel like sleeping with any more white women?” and I knew who they were.

By the CHAIRMAN:

Question. These women, you say, were a low-down class of persons?

Answer. Yes, sir; not counted at all.

Question. Did white men associate with them?

Answer. It was said they did.

Question. Did respectable white men go there?

Answer. Some of them did. Mr. Stokes did before he went to Texas, and several of the others around there. I do not know many men in Georgia any way; I have not been about much. I have heard a heap of names of those who used to go there. I came by there one night, and I saw three men there myself.

Question. You say John Walthall had been going there a good while?

Answer. Yes, sir; that is what they say. Question. How long had he quit before they killed him?

Answer. A year before last, a while before Christmas. He was still staying at old man Martin’s. I staid last year close to Carroll, and when I came back he had quit.

Question. Did he go with them any more after he married?

Answer. No, sir; be staid with his wife all the time. He lived next to me.

Question. How long had he been married before he was killed?

Answer. They married six weeks before Christmas, and he was killed on the 22d of April.

Source: From Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. Georgia, vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872. 411–412.